ANZAC DAY – THE BIG PICTURE

April 25, 2014

ANZAC DAY WESLEY MISSION FRANK VICKERY VILLAGE, NSW APRIL 25 2014

“Europe’s Century”

This year begins the 100th anniversary of World War I. It will run on for four years and Australia alone is spending about a third of a billion dollars on the anniversary. I think that this level of expenditure is justified because it is important that we remember our history.

Back in 1914 there was a general feeling in Europe that the 20th century was destined to be another grand century of world affairs dominated by Europe. Europeans controlled most of the world through their colonial empires. It was the centre of economic, social and technological progress.

The UK had gone for 99 years without a major land war (the Napoleonic Wars had ended in 1815 with the Battle of Waterloo). The Royal Navy had not had a major conflict since the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 when France was defeated at sea. It had ruled the waves for over a century. It had made good use of its authority via the elimination of the slave trade by sea (slavery itself alas continues to this day).

Within the next four years Europe was transformed. By 1918 many of the European monarchies had been swept away. This was the end of Queen Victoria’s dream whereby she and her beloved Albert hoped that by marrying their children into the European ruling houses, there would be less chance of a European war because all the rulers would be related by marriage. Alas the crown heads may have been related but the real power was with other leaders – and they wanted war.

Also by 1918 the two countries that really were to dominate the globe for the rest of the 20th century were getting into place. The US was forced into the war in 1917 and so ended its policy of Isolationism (at least for awhile). The Russian rulers were replaced by the communists, also in 1917. The US and Soviet Union were to be the key countries for much of the 20th century.

1914 was, then, a reminder of just how quickly an apparently stable global situation can be transformed. You can never just what is around the corner.

“All Over by Christmas”

Both sides expected a quick victory. Economists had warned that a modern European economy could not withstand a long conflict. No one predicted that the war could last for four years.

But in fact a stalemate quickly developed on the Western Front (which ran from the North Sea down to Italy).

It was in this context that the Allied leaders looked to a campaign in eastern Europe to create a new “front” and so help end the stalemate.

The imaginative approach would be an attack on Turkey, with the Allied forces getting to Constantinople (present day Istanbul) pushing the Ottoman Empire out of the war creating a new front against Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the east, thereby also forcing through a new supply route up to the embattled Russian Empire through the Black Sea. (The UK’s naval northern route across the North Sea was very dangerous – indeed a military architect of the 1915 Gallipoli campaign, Field Marshal Kitchener, perished on that route while sailing to the Russian Empire in June 1916).

It is a matter of speculation of what European – and world – history could have been like if the Gallipoli campaign had been successful.

The Gallipoli Disaster

But the campaign was a disaster. Amphibious operations are always risky – hence their comparative rarity in military history. This was the most ambitious one in British history up to that point. It required a high level of cooperation between the navy and army – and there was then little tradition of that in any European military force.

At the strategic level, there was too much optimism about what could be achieved with the limited resources devoted to the campaign. We will never know if victory could have been achieved if the campaign had received more supplies and better leaders.

At the tactical level, this was a new type of warfare. There were problems with the weather, a lack of good food and water, various diseases were in circulation, and there was inadequate clothing.

Ironically the withdrawal by sea was done perfectly, with not one soldier lost. The campaign was over by December 20 1915.

Winston Churchill’s political career was a Gallipoli casualty. Scapegoats had to be found for the failure and – as the navy minister – he was pushed out of office (a later prime minister called him back from military service on the Western Front and rehabilitated his career). But Churchill remained haunted by the Gallipoli disaster for the rest of his life.

2014 will also be the 70th anniversary of the June 1944 D Day landings in France. The US was forced into World War II by Pearl Harbour in December 1941 and was soon pressing for an amphibious invasion of Europe. After all, back in 1917 the war ended about a year after the US was forced to get involved, and so the US had equally high hopes for a quick end to Hitler.

But Churchill knew better. He had had an experience of a risky amphibious operation at Gallipoli and did not want to risk another failure. A long-term benefit of Gallipoli was, then, Churchill’s hesitation about any hasty invasion of Europe. He wanted extensive preparations made and adequate resources devoted to the cross-Channel invasion.

The losses at Gallipoli therefore helped reduce the losses in June 1944, whose success opened up the final chapter of World War II.

99 Years On

The role of warfare is now very different. The world is a much safer place in 2014 than in 1914. This may not be obvious from the media’s interest in warfare. But in fact the most dangerous time to have lived between 1900 and 2014 was 1900 to 1950. Since 1950 (with the outbreak of the Korean War) there has been a gradual decline in the number of wars and the number of people killed in wars.

Countries now often prefer to trade rather than fight. France and Germany – whose mutual hatred for over a thousand years – has stained European history and drawn Australians into two World Wars, have now gone for over six decades without another war. It is inconceivable that they would now go to war against each other.

Meanwhile, commemorating the Gallipoli campaign provides an entry route into the much larger history of Australian involvement in World War I.

Five times more Australians served on the Western Front than at Gallipoli and five times as many died there. Australia also produced one of the best generals of the war: Sir John Monash. Although Australians on the Western Front represented less than 10 per cent of the Allied forces, they captured about 25 per cent of the enemy territory, prisoners and weapons.

Hopefully the extensive commemorations of World War I over the next four years will put the Gallipoli campaign into a wider perspective.

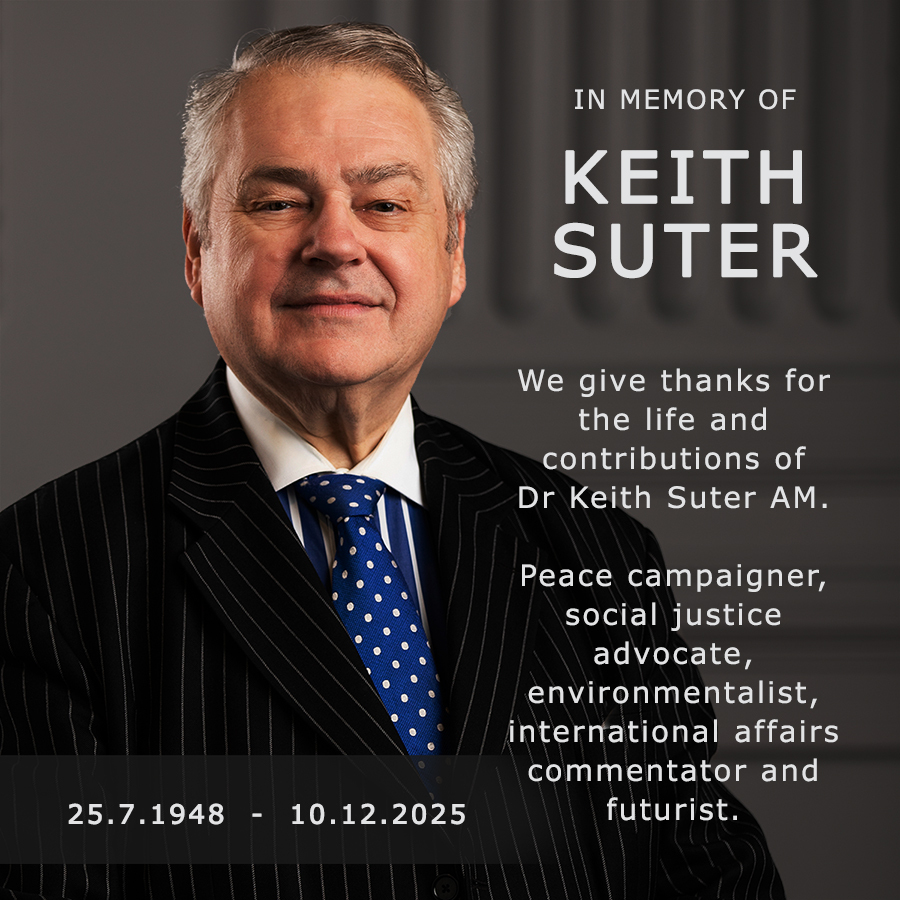

Written By: Keith Suter, Managing Director www.Global-Directions.com